![An artist's depiction of Eleggua as a young child.]()

An artist’s depiction of Eleggua as a young child.

There seems to be a big misconception in online communities about who Eleggua is, how he’s related to Papa Legba, or Eshu, or even Exu. All too often, our western minds see similarities and draw equivalences between these entities but doing so is a big mistake. After a friend asked me what the difference was between these spirits, I decided to contact my friends in two other African Diasporic religions: Hougan Matt (Bozanfe Bon Ougan) a Hougan Asogwe of Haitian Vodou and ConjureMan Ali (Tata Alufa Mavambo Ngobodi Nzila) a Tata of Brazilian Quimbanda, and asked them to share their scholarly expertise to the following questions. Answers are listed side by side and color coded with Houngan Matt’s answers in blue, ConjureMan Ali’s answers in red and Rev. Dr. E.’s answers in green.

Just to clarify, Legba is from Haitian Vodou, Eleggua/Eshu is from Santería Lucumi (and consequently Yoruba religion) and Exu is from Brazilian Quimbanda (and Umbanda). These are three different classes of spirits and he offer this information here for you to understand the difference between them.

Who are you and in which tradition do you participate?

Houngan Matt: Im Matt Deos, known either as Houngan Matt or by my ritual name Bozanfe Bon Oungan, and Im a Houngan Asogwe (senior ranking clergy initiate) of a traditionalist Haitian Vodou house known as Sosyete Nago (based in Boston, MA and Jacmel, Haiti, and run by my spiritual mother Manbo Maude/Antiola Bo Manbo)

ConjureMan Ali: I am ConjureMan Ali, a conjure doctor, djinn conjurer, and a Tata in the Afro-Brazilian tradition of Quimbanda

Rev. Dr. E.: I am Rev. Dr. E. or known by my initiatory name of Ekun Dayo. I am an olorisha (priest) crowned with Changó in the Afro-Cuban religion of Santería (La Regla Lukumí). I am founder of the Santeria Church of the Orishas and a full time conjure doctor.

Who is Legba, Eleggua, Eshu, Exu?

Houngan Matt: (Regarding Legba) The Legba spirits, in Vodou, are a family of lwa who each are responsible for “opening the door” or initiating access to each section, or ritual division, of spirits that are served in our rites. Each nancion, or nation (a term used to distinguish groupings of lwa by their home culture or the people whose spirits they were before those people were brought to Haiti as slaves) has its own door-opening spirit referred to as a Legba. There are many such corresponding divisions of lwa, and each has their own Legba tasked with opening the door and allowing those spirits to pass. The Legbas are spirits of communication and contact, removers of barriers and openers of doors, who speak all languages and know all forms of communication.

In a fete, one of the Legba spirits is always among the first spirits sung for and invited to come to the party with us… but there’s a good deal of misconception out there about what this means. Contrary to internet-misinformation, when the priye ginen (our litany of prayer and song that blesses and begins all services) is complete, the first spirit we sing to is Hountor, the lwa of the drums, who translates our modern speech and song into the tonal language of the drums, the ancient spirit-speak us Creoles no longer shape with our mouths. Then, we sing into being Grand Chemin, the Great Road that bridges our place of ceremony and the land where the spirits reside… a great and golden road the lwa proceed down to come to our temple (and, often, also the poto mitan, the central axis of the temple which our spirits can ride).

Legba nan Rada, or Legba in the Rada Rite, is the first of the Legba spirits we serve, and his task is to open the gate on the Great Road, the doorway that allows the other spirits to come to our celebrations and rites. Without him, there wouldnt be a gap or a coming-together-place where our world and the world of the spirits could touch.

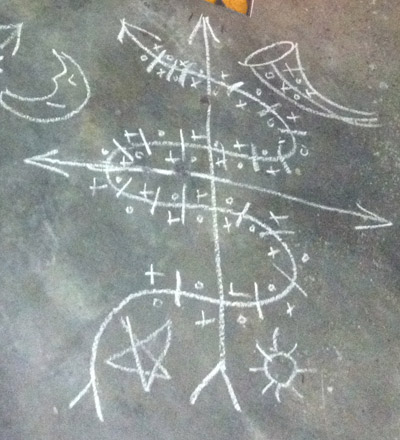

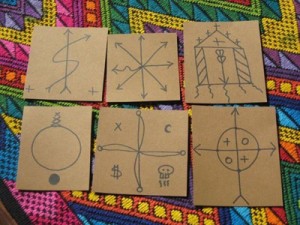

In Vodou’s language of visual symbols that convey meaning, the imagery used to represent the various Legba spirits always features the symbol of the Poto Mitan in some way or form as it is the doorway on the Great Road that Legba controls. For my lineage, the Rada Legba wears a saint known as Saint Anthony the Abbot (a jovial and well-fed man in brown robes, holding a staff, the poto mitan, and standing at a cave door, surrounded by animals such as pigs and chickens). Legba nan Petro, the Legba who opens to doorway for the hotter and rougher spirits of the Petro rite, wears the image of Saint Lazarus (typically an emaciated and sometimes bruised man walking by means of crutches, another symbolic stand-in for the Poto Mitan).

Even the nations that make up the components of the larger Rada and Petro rites also have their Legba figures (who may or may not be members of the Legba family of spirits… often times, Ogou Ossange, a wonded healer who is also always shown with crutches, can serve as the Legba nan Nago, or the Legba figure who opens the door for the Nago nation spirits, or the division that holds the spirits of the Nago people, who are now more widely known by the name of their language, Yoruba.)

The Ghede family, the spirits that are called at the end of every Vodou celebration, also have their own door keepers/Legbas of their group… and are also known for carrying a Baton Ghede, a walking stick that can alternately be a gentlemen’s cane or be placed between the spirit’s legs as the source of many embarrassing jokes… but which is also, in its way, the Poto Mitan and the road by which the spirits in the Ghede’s purview travel.

In Haitian Vodou, the Legbas are not Crossroads spirits; the way our rites work, the road by which the fiery Petro spirits are brought into the rites is conceptualized as being at a 90 degree angle to the cooler road by which the Rada lwa enter. When the Petro rites have begun, songs are sung for Dan (or Don) Petro (mythologized as the creater of the Petro system, but basically the Grand Chemin figure of the new cosmological angle of approach), then comes the Petro Legba, and after a few more spirits the rite reaches Kalfou, the lwa who is the crossroads made manifest (Kalfou is a creolization of the French Carrefour, literally crossroads). To us, the Legba figures are the keepers of gates and doors, languages and communication… not the crossroads, which we have as a different being entirely.

![An artist's depiction of Exu Veludo, one of the Exus of Brazilian Quimbanda]()

An artist’s depiction of Exu Veludo, one of the Exus of Brazilian Quimbanda

ConjureMan Ali: (Regarding Exu) Exu, pronounced “Eshoo” in Quimbanda is not a singular entity, but a class of spirits that are connected to the Congo and Angolan cults of sorcery and necromancy that took root in Brazil after slaves were brought over by the Portuguese. It would be more accurate to view Exu as a title referring to a class of fiery spirits called upon in the Afro-Brazilian cults for matters of guidance and to work magic. Each Exu is unique and the personalities can vary drastically from one Exu to another. Regardless of the differences what is common is that Exu is a highly dangerous, fiery, and tricky spirit to work with. Exu is not an Orisha, or Lwa, but are earthly guardians of the liminal who are both a force of nature as well as spirits of the dead.

Rev. Dr. E.: (Regarding Eleggua/Eshu) First we must distinguish between Eshu and Eleggua. Eshu (spelled Esu in traditional Yoruba with a little dot under the “s”) are a family of orishas more like natural forces. Eshus are found everywhere in the wild and each is different from the others. Eshus are wild and uncontrollable by nature. Messing with one without the proper respect will get you in big trouble quickly as it is the nature of Eshu to cause problems, test humanity and upset the balance of things. Babalawos are experts at working with an controlling Eshu for the betterment of humanity. They have the spiritual technology to tame Eshu.

Eleggua (or Elegba) – to contrast – is an orisha that can be considered to be the king of the Eshus. He is refined; civilized if you will. Eleggua is an orisha that has many roads each of which is called “Eshu” (to further confuse the issue). There is an Eleggua that wanders in the wilderness. There is an Eleggua that lives in the river. There is an Eleggua that lives on the road. There is an Eleggua that lives in the house. There are over a hundred different roads of Eleggua and each is different from the others, with different temperaments and different likes. There is one thing in common with all Elegguas – they are always honored first amongst the orishas whenever we have a ceremony.

Eleggua knows everything, witnesses everything and has the key to changing our destinies as humans: ebó (sacrifice). He is the one that can speak for all of the other orishas because he knows everything that’s going on. Eleggua is considered one of the warriors in our religion along with Ogun, Ochosi and Osun (as well as Erinle and Abata). He opens the road to all things and makes the spiritual connection of ache happen between humans, Olodumare, the orishas and the ancestors. Without Eleggua nothing would get where it is intended to go. Because of this we say you must always be in his graces or he’ll shut you down in no time.

Where does the worship of Legba/Eleggua/Exu originate?

Hougan Matt: (Regarding Legba) The Legba spirits are an intrinsic piece of the religion of the Fon people of Dahomey (and modern day Benin) whose cosmology forms the majority of Vodou’s metaphysical foundation. (Even the word Vodou comes from the Fon word meaning “spirit”; Lwa in turn is the Fon/Gbwe word for “lord”) Their religion continues in its homeland, now usually known as Beninois Vodou.

Among the Fon people, Legba is featured as being both the favorite and youngest son of Mawu/Lisa (the Creators/high gods), responsible for the writing (Fa, or destiny) of each man’s life. Within Dahomey, however, Fa is also a vodun (that word for “spirit”), to whom one goes in order to divine, and Legba is his servant. Legba plays a central role in Dahomean society, where it was necessary to divine, or consult Fa (through Legba) before one did anything and about all things. The Dahomean Legba is a young man, youngest son of the Creator deities, and combines ideas that when they reached Haiti would divide into the Legba family of spirits (as well as provide the foundation for the Ghede spirits as the Dahomean Legba changed from a younger man to an older grouping of men, and as the boundary between life and death was divided into multiple spirits instead of being held by their original gatekeeper. Fusing with Taino spirituality in Haiti, the trickster/healer/death aspects of Legba in Dahomey gave birth to the Ghede spirits who maintain the boundary between the living and the cemetery…. itself a crossroads where the living and the dead intersect, with their own crossroads keeper Met Cimitiere, sometimes seen as Petro and sometimes seen as within the Ghede family)

MANY pieces of the Dahomean Legba (the Root legba, if you will) changed with the combination of many different Kingdoms’ religions that happened in Haiti, on its plantations and as a result of the Revolution that made a single united Nation out of the many slaves who rebelled and forced their French overlords off the island in bloody revolt. Knowing there was no way “home” to their ancestral Africa, the new Haitians blended their religions together to keep them from being lost, and the many different manifestations/individual traditions of Haitian Vodou were born… but, in the process, many spirits took new aspects to their personalities and many new needs were filled by spirits who emerged. New Legba figures emerged to open the doors to spirits of new and different populations that took their place among the other spirits of the newly emergent and uniquely Haitian Vodou.

ConjureMan Ali: (Regarding Exu) Exu’s roots are found in the Angolan and Congo cults of Kalunga, Kadiempembe, and Pambujila. He emerges from a fusion of death, fire, and the crossroads. The descendent of these forces is then Exu who finds his home in the Afro-Brazilian religion of Quimbanda. It is important to note, that Exu exists only in South America, starting in Brazil and slowly expanding to neighboring countries, he is not found in any of the North American African Traditional Religions and has nothing to do with Lukumi, Vodou, Palo etc.

![Eleggua in the traditional hand-molded cement head form in Santeria Lukumí (This is Eshu Alawana)]()

Eleggua in the traditional hand-molded cement head form in Santeria Lukumí (This is Eshu Alawana)

Rev. Dr. E.: (Regarding Eleggua/Eshu) Eleggua and Eshu’s roots are in the west african Yoruba people who lived in the area currently associated with southwestern Nigeria and Benin. They were universally revered throughout all of the tribes that spoke the Yoruban language. The slaves that were taken from the Yoruba lands and brought to Cuba brought the veneration of Eleggua/Eshu with them. The understanding of Eleggua as separate from Eshu evolved in Cuba within the Santeria religion. Eleggua and Eshu are seen as pretty much one and the same back in Africa and this may be due to the prominence of the Ifá sect of Babalawos in the motherland versus their late arrival in large numbers in Cuba. To be very clear, Eleggua is not found in Vodou (although the Lwa from the Nago Lwa are technically the same as the orishas, he isn’t worshipped in the same manner as we do), he is not found in New Orleans Voodoo although some modern-day practitioners are attempting to culturally appropriate him for their benefits, and he is not part of Palo Mayombe. He is an orisha, not a lwa, not a mpungo, and not a spirit of the dead.

Is there any ritual or initiatory requirement to work with Legba/Eleggua/Exu?

![Houngan Matt (Bozanfe Bon Ougan) is a Houngan Asogwe of Haitian Vodou]()

Houngan Matt (Bozanfe Bon Ougan) is a Houngan Asogwe of Haitian Vodou

Houngan Matt: (Regarding Legba) Nope. ![:-)]() Well, almost. In terms of initiatory requirement, no… as the Legba spirits govern communication with the rest of the spirits, ALL people are seen as inherently having a connection with these Lwa (unlike the others, which may or may not be “with” a person and whose presence “with” a person must be determined by divination).

Well, almost. In terms of initiatory requirement, no… as the Legba spirits govern communication with the rest of the spirits, ALL people are seen as inherently having a connection with these Lwa (unlike the others, which may or may not be “with” a person and whose presence “with” a person must be determined by divination).

As all of us are born with an ability to serve those spirits we inherit or who seek to build relationships with us (those that pop up in that aforementioned divination) ALL of us have access to the Legba spirits, either for opening those doors and forging roads of communication and respect, or for working with the way we would any spirit we serve.

In terms of ritual requirements, yes… to work within Haitian Vodou requires keeping to Haitian Vodou’s ceremonial protocols, rules, and heirarchies. We are not a freeform religion, but one that has a very solid cosmological core and an associated body of traditional rites, songs, and methods of ritual. Not everyone needs to become an initiate to work with their spirits in our religion, but our religion is guided by its priests to maintain its lore and the integrity of its tradition and systems; in a similar vein, not all Catholics need to be priests, and certainly one does not need to be a priest to say the Rosary in home prayer… but for transmission of the faith, the services of the priesthood, and the offering of Mass, the clergy is required. Vodou is much the same in how it works and functions, and the faithful, while they are capable of small acts of service to their spirits at home, also understand that the faith is a community religion that requires the community of priests and laypeople alike in community celebrations to function at anything beyond its most basic level.

![ConjureMan Ali is a Tata of Brazilian Quimbanda and founder of the House of Quimbanda church.]()

ConjureMan Ali is a Tata of Brazilian Quimbanda and founder of the House of Quimbanda church.

ConjureMan Ali: (Regarding Exu) Yes! Exu has a strong sense of respect and honor. In order to call upon Exu, there are set ways that they demand you approach them. It is also the safest way to work with them, for without the context of protection provided by following these well-worn roads, you risk burning yourself. It is like playing with fire. In Quimbanda, there are levels of involvement that one can participate it. Initiation is for those who are called to be priests and priestesses. Not everyone is called to that path. One can also be a licensed medium through a baptism ceremony, or licensa. In this case you can then safely work with your personal Exu and Pomba Gira. Finally, anyone can benefit from finding out which Exu or Pomba Gira form the spiritual court of your life through divination. This latter is only to find out about them and does not require any obligation nor do you need to get involved further. It is basically taking a look behind the curtain. For further involvement, you will need to look at licensa or initiation.

With licensa you take your personal Exu and Pomba Gira as your patron and work with them in a spiritualist or devotional context. You work with those spirits that walk with you and develop a relationship with them which has many benefits. Initiation however is a more intense path with much obligation and so is not meant for everyone. The initiated Tata or Yaya is granted the Keys to the Kingdom of Quimbanda and while the core of their spiritual court is their personal Exu and Pomba Gira, they will become a priest to the entire Kingdom with many spirits working with them. It is also the initiated Tata and Yaya who work as the sorcerers and sorceresses of the cult.

Without either licensa or initiation, calling upon Exu can be quite dangerous. There is a unique format to their rituals that is only taught through the guidance of a House or terreiro of Quimbanda. Without this format you aren’t calling Exu, you are simply opening yourself up to any spirit walking by to come into your life.

![Rev. Dr. E. (Ekun Dayo Oní Changó) is an Olorisha in Santería (La Regla Lukumí) and founder of the Santería Church of the Orishas.]()

Rev. Dr. E. (Ekun Dayo Oní Changó) is an Olorisha in Santería (La Regla Lukumí) and founder of the Santería Church of the Orishas.

Rev. Dr. E.: (Regarding Eleggua and Eshu) Yes and no. Anyone can give offerings of the heart or veneration to the orishas in nature. For Eleggua or Eshu this would be the places where he can be found: the side of the road, the wilderness, the cemetery, the edge of the river, the ocean, the crossroad, almost anywhere – but keep in mind that different Eshus and Elegguas are found in different places. But this is a personal offering made for yourself and you must act carefully as to not offer Eleggua or Eshu something that they wouldn’t like. Guidance of a godparent is probably the best idea in this situation.

It is highly improper and offensive to the orishas to act in the office of a priest or priestess doing work for others without being an Olorisha or a Babalawo. You don’t have the lineage to call upon if you aren’t initiated and as such do not have the support of the ancestors and even they come before Eleggua!

You need to be an Olorisha or a Babalawo to have received the ritual items and shrines of Eleggua or Eshu. This is a highly involved ritual and requires divination before going through it. It’s not something you receive because you want it. It’s something you do because divination says it’s part of your destiny and you need it. Once you have been ordained as an Olorisha or a Babalawo you can then divine with Eleggua’s shells, make ebó (sacrifice and rituals) to Eleggua and act as an intermediary between the general public and Eleggua or Eshu.

How can a person revere Legba/Eleggua/Exu and pay homage to him?

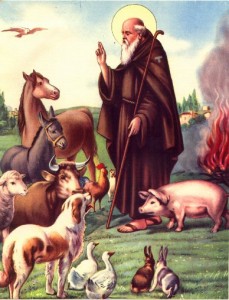

![Saint Anthony the Abbot - an image used to depict Legba in Houngan Matt's lineage]()

Saint Anthony the Abbot – an image used to depict Legba in Houngan Matt’s lineage

Houngan Matt: (Regarding Legba) Easily! If a person is interested in establishing working relationships with their spirits through Vodou’s traditions and paradigm, the Legba spirits are going to be some of the lwa they’ll be speaking to most!

I recommend starting by reaching out to qualified initiate clergy for advice, or seeing if there is a House (initiate family of priests who offer community celebration of the lwa to the public in their area) that can help guide the new person (as well as make sure there are folks nearby who can help the new person if things go wrong or become unbalanced), but while that’s happening, the Rada Legba is immediately approachable (ESPECIALLY as a fantastic spirit too ask to help convey the new person to a reputable house!)

I recommend seeking out the image I spoke of before, of Saint Anthony the Abbot (this is not Saint Anthony of Padua, who holds the infant Jesus. Instead this is the staff holding monk standing before a cave, surrounded by happy animals, and the image can be found through a google image search and printed out) and possibly creating a small working altar (in a clean place outside one’s bedroom, or able to be screened from view if the bedroom is the only possibility) decorated in cloths of white, red, and brown (white for all Rada spirits, and Red and Brown are the colors of the Rada Legba in my lineage). The altar should also have a glass of cool, clean water, white candles, a crucifix (a strand of rosary beads works in a pinch) and a space for simple offerings such as flowers, fruits, florida water, or specific foods.

Catholic prayers are recited first, to give thanks and recognition to God and to ask him to bless the service, making sure only His clean spirits are allowed to enter. Typically these prayers are an Our Father, three Hail Mary’s, the Apostle’s Creed, the Confiteor, the Act of Contrition, and a Glory Be. Once those are said, offerings can be made and you can talk to Legba about your needs and check in with him; preferably once a week on either a Saturday or a Monday. Ideally you’d take some time to learn the saluting protocols and motions/choreography to salute a Rada lwa (instructions for a basic Rada style salute are available in an indepth article on my teaching blog, found herehttp://blog.vodouboston.com/2011/07/jete-dlo-basic-salute/)

Favoured offerings of the Rada Legba are red and white flowers, roasted root vegetables such as potato, yam, and sweet potato, cassava bread, and a mixture of pan toasted (but not popped) corn kernels and peanuts. The Rada Legba in my lineage takes poured offerings of white rum as his favoured beverage, and also likes material gifts of straw hats, pipes, and plain pipe tobacco.

Clergy guidance is strongly encouraged.

ConjureMan Ali: (Regarding Exu) We honor Exu, but we do not worship Exu. This is a very important distinction to make as God, or Nzambi, is the only figure that worship is given to. In Quimbanda, one does not give homage to Exu randomly, but has to find out which Exu specifically walks with you. Because there are countless Exu, you cannot simply decide to light a candle to one, or pray to him. This invites a great deal of trouble as it opens the door to all sorts of trickster and parasitic spirits. It is essential to first find out which Exu walks with you through the divination provided by an initiated medium or priest who can then instruct on how a proper relationship can be formed.

Rev. Dr. E.: (Regarding Eleggua and Eshu) No matter what you do it is important to understand that we do not worship Eleggua, we pay homage to him and work with him. We only worship God – Olodumare/Olorun/Olofi. One of the most effective ways to honor Eleggua in your day is to always ask for his blessing when passing his location in nature that you associate with him. So if you work with the Eleggua or Eshu that’s by the side of the river then make sure to say “Agbe mi Eleggua!” or “Bendición Elegguá!” when you pass the river’s edge. That way you show him continual gratitude and make sure he keeps your road open for you. Before you go making fruit offerings or such to Eleggua or Eshu it is imperative that you work with a godparent so that you can be sure you’re offering him the right things in the right ways and in the right places. It is more traditional to work through a diviner (an Olorisha or a Babalawo) to ascertain whether an offering or sacrifice is needed and specifically what kind (as determined in the reading). Only an Olorisha or Babalawo can do this for you.

Some of the safest offerings you can give Eleggua or Eshu are toasted corn, smoked fish, rum and cigars. These are his favorite items no matter what road you happen to be working with. Keep in mind, however, that Eleggua (as with all the orishas) becomes accustomed to the way you treat him. If you break your pattern or change the way you’ve been treating him he will become upset and block up your paths. Many people work with Eleggua every monday by pouring out a tiny libation of cool water and praying to him, but the first monday you miss that routine will be the day that Eleggua really trips you up. So keep that in mind before you start setting up a steady pattern of veneration. Again, work with a godparent for optimal results.

What advice or feedback to you have for people who mistakenly try to draw parallels between or equate Legba with Eleggua, Eshu, or Exu?

Houngan Matt: DONT! The Legba spirits all stem from the Fon people, who are not the same as the nations who carry those other spirits in their own distinct religions. Legba is NOT Eshu any more than the Virgin Mary is Quan Yin; the powers come from separate religions that maintain very separate and distinct cosmological and metaphysical functions.

Even where there may be SOME passing similarity between the spirits (much like the Virgin Mary and Quan Yin are both known in their respective religions as Merciful) the differences in the religions are vast… attempting to blend the systems or cherry pick between them is a deep insult to the spirits who are accustomed to being carried within their traditions (which, over the centuries, THEY have created and guided in their evolutions). Just as Quan Yin would probably herself be horrified to be invoked in a service featuring a divine son’s blood and flesh being offered to a congregation in the form of Catholic Communion, the different spirits known as Legba, Exu, Eshu, and Ellegua would be deeply unhappy at the resulting dissonance of forcing them into boxes where they do not belong.

Im often asked why they seem to serve similar function (which I gotta say after all of my reading they really DONT) but why us priests involved in the different traditions have little heart attacks when people cherrypick and mix… and my best example is modern math and Physics.

We’ve all heard about Quantum Physics, a series of mathematical equations and theories that seek to explain how the world works at its smallest possible level.

We’ve also all heard about Newtonian and Einsteinian systems of Physics, which are mathematical equations and theories that seek to explain how the universe functions on a grand scale of light, distance, speed, and gravity.

Both systems work…. until they’re mixed. The equations are incompatible, the math cannot be justified, and instead of any answers that make sense the equations produce nothing but meaningless garbage.

With our religions, I recommend keeping the same separateness and approaching each as *what it is* instead of trying to shove them into places where they do not belong. Just as in physics, attempting to place Exu in a Vodou paradigm or lifting a Legba spirit out of his home (or worse, calling Ellegua Legba and insisting Legba works through a concrete head that may or may not have been made by it’s own system’s priests) is bound to fail and practically guaranteed to make very unhappy spirits.

When it comes to the spirits that govern not only our communication skills but out ability to maintain relationships with ALL the other spirits of their respective systems, upsetting these guys or trying to make them work as something they’re not is just a UNIVERSALLY bad idea.

A person CAN work multiple systems when properly guided by initiates, but just like our example of Quantum versus Einsteinian physics, those systems need to be kept separate and worked on their own time, NEVER blended.

ConjureMan Ali: Simply put; don’t. Exu is not an orisha, he is not a lwa, he is not a mpungo, he is a being all himself. Furthermore, Exu is from Brazil and he has nothing to do with the African Traditional Religions more commonly known here in North America. Exu is a very territorial spirit who is HUGE on respect, trying to force-fit him into your own preconceived notions, or misconceptions will only anger him and cause trouble.

If you truly are interested in Exu and feel called, then don’t approach with the arrogance that you are entitled to his power. Instead learn about him properly from an initiated Tata or Yaya and house/terreiro and follow the proper paths of working with him. To give an analogy, if you were traveling to a foreign country that spoke a different language and you approached a very important official and demanded that they serve you and they better speak English, how do you think they’d respond? You’d be lucky if you got away with a crossed look. Just as you’d try to learn a bit of the local language, learn the proper customs and protocol, so too must you with Exu. Don’t think you can buy some “Exu poppet” or “Pomba Gira Oil” and you’ll be able to work with them.

Rev. Dr. E.: Just don’t! To people who try to draw parallels between Legba, Eleggua/Eshu and Exu I say “Please remove your European lenses!” Just because things may have similar traits does not mean they are the same being. Chango throws lightning and so, too, does Zeus but they are not the same spirit/god/entity. When you try to draw parallels and create false equivalencies between spirits of different cultures and religions what you’re really doing is simplifying for your convenience (and laziness). Take the time to understand the differences between the cultures. Follow the proper channels and protocols of each culture and religion to honor the spirits therein, and to respect the sacrifice the ancestors made to preserve these traditions in the face of slavery.

If you’re going to work with the orishas, then do so through the religion THEY passed down to us, not in an invention you created out of European traditions and techniques. Keep things separate because they ARE different and they ARE separate from one another. If we painted everything in the same light the whole world would be a boring shade of grey.

Learn More About The Contributing Authors

A special thanks to Houngan Matt and ConjureMan Ali for contributing to this article. We have all agreed to share this article across our three blogs in the spirit of sharing and education. If you are interested in learning more about Haitian Vodou or Afro-Brazilian Quimbanda visit their respective web sites listed below:

Houngan Matt’s Vodou Blog

ConjureMan Ali’s House of Quimbanda